The use of open wells for drinking water has been the norm for perhaps thousands of years. But is water from these wells safe? How are these wells used by the communities that require water as a primary resource for day-to-day life? This article describes the uses of open wells in three locations in El Nido, a popular tourist destination site in the western part of the Philippines.

This articles showcases another example of faculty-directed fieldwork for students that opens new areas for further research and allows the generation of hypotheses. Further, this article presents data that could serve as a reference for future related studies.

In 2014, news broke out that El Nido town, a popular island destination in the Philippines’ western part, had coliform levels 3,000 percent higher than average. Studies conducted in the poblacion area identified sewerage lines as the cause of such a high coliform level. Wastewater from hotels and the residential regions empty into the white beaches and eventually make their way into the coastal waters.

Such a high level of coliform is disturbing. Bacteria commonly found in human beings’ gut such as Escherichia coli can cause many problems when these microorganisms make their way into open wells for drinking water purposes. Life-threatening illnesses such as diarrhea, and consequent dehydration results.

Open Wells for Drinking Water Study

Mindful of what is going on in this popular tourist destination, I assigned a group to look into the matter in my thesis writing class. Specifically, I instructed them to find out the water quality of open wells, among other things, as their study’s focus.

The students obliged and visited three locations in the town on September 8, 2016 (Nawzil et al., 2017). They took water samples from open wells in three barangays, namely 1) Buena Suerte, which is part of the busy poblacion, 2) Maligaya adjacent to it and located inward, and 3) Barangay Masagana, located east of the town (Figure 1).

They packed the water samples and placed them in a cooler for immediate transport to the water analysis laboratory back in the City of Puerto Princesa.

The analysis revealed that all of the open wells have total coliform levels greater than 1,600 MPN/100 ml. This result means that the town’s coliform levels improved a little more than half its previous level in 2014. Still, this coliform level can cause illness among the residents.

Major Uses of Water in Open Wells

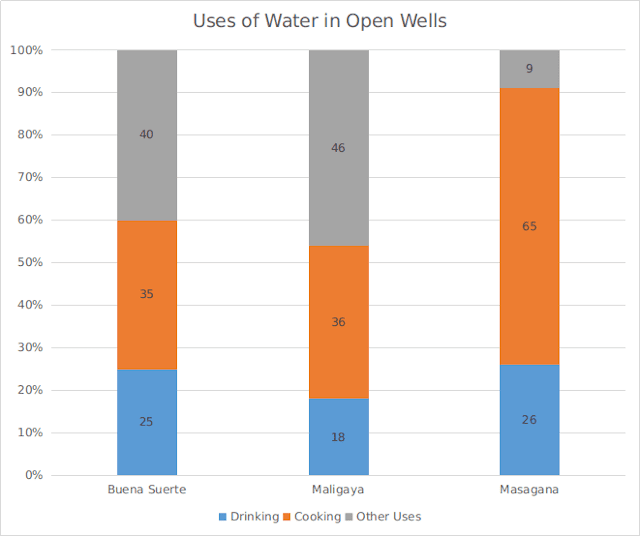

The major uses of the open wells include drinking and cooking. I summarize these uses in the three barangays in Figure 2.

Visual inspections show that about a fifth of the open well’s use is for drinking water. Notice that in Barangay Masagana (third column), water for cooking purposes is almost double the percentage of the same service in Buena Suerte and Maligaya.

Why is this so?

If you refer to these wells’ location in Figure 1, notice that the area bounded by Maligaya lies at the margins of the sandy delta where most of the houses are located. It has a relatively narrow beach bounded by higher mountainous and forested elevations on the eastern side.

The results suggest that wastewater from domestic and commercial establishments quickly make their way into the groundwater through the beaches and unpaved roads. The white, sandy substrate’s porous nature allows infiltration of coliform, mixing with water used by the coastal villagers mainly for drinking and cooking.

Hypotheses Generated from the Study

This simple analysis of existing data on open wells for drinking water and other uses gathered by the students can generate two hypotheses:

- Groundwater along the margins of the beach zone becomes less polluted as you go inland.

- The substrate of the dwelling areas significantly affects the infiltration capacity of contaminated wastewater into the groundwater.

These two hypotheses tentatively build upon the fact that in a deep well in Barangay Maligaya, a test revealed that the coliform level is 240 MPN/100 ml. This value is about 1/6th of the coliform values in other wells, indicating less infiltration of coliform in the ground’s deeper regions.

Conclusion

The study results on the open wells of El Nido opens up areas for a more rigorous study. Although the health aspect of the high levels of coliform in the municipality was not explored in this study, such levels serve as a warning sign that water from open wells poses a clear danger to the residents’ health.

Since a significant percentage of the populace depend on the open wells for drinking and cooking, sterilization procedures need to be made before final water consumption. Such actions can avert costly medical attention or illness that may be prevented with knowledge of the current state of water quality.

Reference

Nawzil, Y. B., Magbanua, I. G. G., Ancheta, D. R., Reyes, R. M., Garay, H. G., and P. M. Cario (2017). Health Economic Value of Coliform Bacteria in the Deep and Open Wells of El Nido Poblacion. Unpublished undergraduate thesis.

© P. A. Regoniel 13 December 2020

[cite]