Given the current issue of blatant corruption in flood control projects in the Philippines, I am compelled to write this article as an educator. Education reforms through ethics education may serve as long-term measures to prevent the deliberate and seemingly callous behavior of those involved—whether government workers or inept politicians—whose actions have wasted public resources intended for the welfare of society.

This article is dedicated to graduate students in public administration, as well as curriculum planners, teachers, and policymakers who wish to institute long-term initiatives that will help build a corruption-free society. A sample policy brief is provided in the latter part of this article.

This article demonstrates how an education theory is applied in curriculum design. I adopted Paulo Freire’s theory of education as the foundational framework for designing a curriculum that addresses the persistent issues of corruption. I also recognize that education reform is a long-term endeavor—one that may take years, even decades, to yield the desired outcomes.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Corruption remains one of the most pressing governance challenges worldwide. It undermines economic development, weakens democratic institutions, and erodes public trust. Conventional anti-corruption measures—such as punitive laws, audits, and enforcement agencies—though necessary, have often proven insufficient. A more sustainable, long-term approach lies in shaping the values and integrity of the younger generation through systematic ethics education and anti-corruption training.

A recent systematic review of literature on the role of education in shaping the integrity of the young generation showed the importance of moral education, anti-corruption training, and integrity development, which are interrelated in the character-building of the younger generation (Suwastika et al, 2025).

Drawing from Paulo Freire’s theory of education, this article argues that transformative ethics education can empower young people to become critical, morally grounded, and socially responsible citizens. The ultimate goal is not only to reduce corruption but to cultivate a society in which corruption becomes socially unacceptable.

Using Paulo Freire’s theory of education, this article:

- explains the foundation for designing a curriculum that fosters a generation of upright learners,

- proposes a curriculum for integrity and anti-corruption,

- presents a diagram illustrating the path to a corruption-free society, and

- provides a downloadable policy brief example to support education reform.

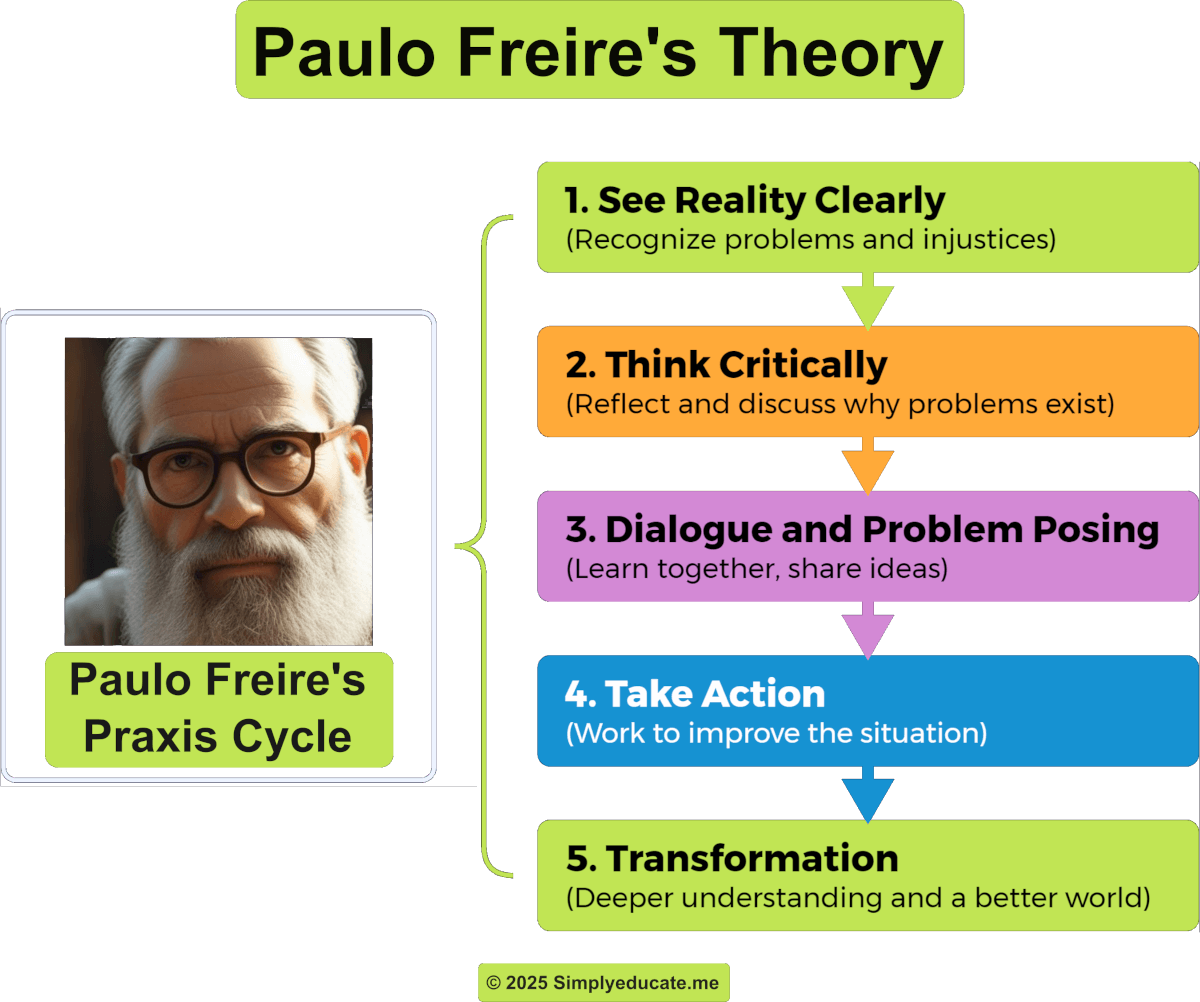

Theoretical Foundation: Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of Transformation

Paulo Freire’s pedagogy emphasizes dialogue, critical consciousness (conscientização), and praxis (reflection and action). Applied to ethics and anti-corruption education:

Dialogue

Instead of passively absorbing information through one-sided lectures, learners are encouraged to participate in open and reflective discussions on ethical dilemmas and corruption. Dialogue allows them to critically examine real-life situations, voice their perspectives, and challenge assumptions.

In this interactive process, students not only acquire knowledge but also develop the confidence to articulate values of honesty, fairness, and justice in contexts that mirror society.

Critical Consciousness

Through guided reflection and case analysis, students learn to go beyond seeing corruption as merely the fault of individuals. They begin to recognize corruption as a systemic issue rooted in socio-political structures, power imbalances, and institutional weaknesses.

This heightened awareness—what Paulo Freire calls conscientização—empowers learners to identify the deeper causes of corruption and to question cultural norms that may tolerate or even enable corrupt practices.

Praxis

True learning, according to Freire, occurs when reflection is paired with action. Education should therefore inspire concrete steps: young citizens internalize ethical principles, integrate integrity into their daily decision-making, and actively resist participating in corrupt practices.

Praxis may take the form of student-led anti-corruption initiatives, civic engagement projects, or public campaigns that promote transparency and accountability. In doing so, learners move from awareness to active agency in shaping a more just society.

Freire’s model thus shifts ethics education from rote learning to a transformative process of empowerment. Dialogue, critical consciousness, and praxis shift the role of ethics education from rote memorization of moral rules to a transformative process of empowerment.

Students are not merely taught what is right or wrong; they are equipped with the capacity to analyze, reflect, and act against corruption in ways that contribute to building a culture of integrity.

Designing a Curriculum for Integrity and Anti-Corruption

A systematic ethics education curriculum should cut across all levels of schooling—from primary to higher education—and include the following four dimensions:

1. Moral and Ethical Foundations

Content

Philosophy of ethics, moral reasoning, cultural values, religion and ethics, principles of justice.

Approach

Case-based learning, reflective essays, values clarification exercises.

2. Anti-Corruption Awareness and Training

Content

Definition and forms of corruption, causes and consequences, international conventions (e.g., UNCAC), national laws, whistleblower protection.

Approach

Simulation exercises (e.g., handling bribery scenarios), interactive workshops, role plays.

3. Integrity Development through Civic Engagement

Content

Civic responsibility, leadership and accountability, transparency in governance.

Approach

Student-led anti-corruption campaigns, service-learning projects, community immersion.

4. Institutional Integration and Policy Support

- Ethics modules embedded in all disciplines (not just public administration or law).

- Teacher training programs to equip educators with skills in ethics facilitation.

- Institutional codes of conduct enforced in schools and universities.

Curriculum Framework

A transformative curriculum on ethics and anti-corruption must be both age-appropriate and progressive, allowing learners to internalize values at each stage of development. The framework below outlines learning objectives, teaching methods, and assessment strategies designed to gradually shape a generation of citizens committed to integrity.

Learning Objectives (by level of education):

Primary Education

At this stage, the focus is on instilling basic moral values that form the foundation of ethical behavior. Children learn to recognize the difference between right and wrong and practice honesty in everyday activities such as sharing, fairness in games, and respecting rules.

Simple stories, fables, and classroom activities provide opportunities to reinforce honesty and empathy.

Secondary Education

Adolescents are introduced to the concept of corruption and its harmful effects on society. Through case studies and class discussions, they develop the ability to apply moral reasoning to real-life situations, such as academic dishonesty, cheating, or small-scale bribery. The emphasis is on making ethical choices in their daily lives while understanding the broader social consequences of corruption.

Tertiary/Graduate Education

At the university level, particularly in fields like public administration, political science, and business, students engage in advanced critical analysis of governance structures, institutional weaknesses, and policy gaps. They are tasked with developing evidence-based policy recommendations and are encouraged to practice ethical leadership in both academic settings and real-world internships.

The ultimate goal is to prepare graduates to become reform-minded professionals capable of resisting and addressing corruption in governance and society.

Teaching Methods

- Dialogical learning (debates, forums, group reflection).

- Problem-posing education (students analyze corruption cases in context).

- Experiential learning (internships in government or NGOs with integrity monitoring).

Assessment

- Portfolios of ethical decision-making cases.

- Community integrity projects.

- Reflection journals on personal ethical growth.

Policy Recommendations

For policymakers, institutionalizing ethics education requires a multi-dimensional approach that combines curriculum reform, teacher development, community engagement, accountability mechanisms, and cross-sector collaboration.

The following measures are essential:

National Curriculum Integration

- Mandate the inclusion of ethics and anti-corruption education at every stage of formal schooling, from primary to tertiary levels.

- Ensure that integrity and ethical values are not treated as standalone subjects but are integrated across disciplines such as social studies, public administration, business, law, and even science and technology.

- Align the curriculum with national development goals and anti-corruption policies to create coherence between education and governance.

Teacher Training Programs

- Develop specialized training modules to prepare teachers for facilitating ethical discussions, role-playing scenarios, and problem-posing exercises.

- Provide continuous professional development opportunities on innovative pedagogies for ethics education, with emphasis on Paulo Freire’s dialogical and transformative methods.

- Introduce a certification system that recognizes teachers who specialize in integrity education, encouraging professional growth and accountability.

Incentivized Community Engagement

- Establish grants, academic credits, or recognition awards for student-led projects that promote transparency, civic participation, and accountability.

- Encourage schools and universities to adopt service-learning frameworks, where students partner with communities and local government units to address real ethical and governance challenges.

- Build a culture of integrity by linking school-based projects with broader national campaigns, ensuring student initiatives contribute to systemic change.

Monitoring and Evaluation

- Develop clear, measurable indicators of student progress in integrity development (e.g., surveys on ethical decision-making, tracking involvement in civic integrity projects, qualitative assessments of reflection journals).

- Link these education indicators with broader governance indices, such as transparency scores and corruption perception metrics, to measure long-term social impact.

- Require schools and universities to submit periodic reports on integrity-related initiatives, ensuring accountability and continuous improvement.

Partnerships

- Collaborate with civil society organizations, which often lead grassroots anti-corruption campaigns and can provide practical insights for students.

- Engage religious organizations, many of which have strong moral and ethical influence, in reinforcing messages of honesty, accountability, and integrity.

- Partner with international agencies such as UNESCO, UNDP, and the World Bank for curriculum support, funding, and access to best practices in anti-corruption education.

- Encourage public-private partnerships where businesses support integrity programs in schools, thereby aligning educational goals with corporate social responsibility.

These policy measures emphasize that ethics education is not simply about teaching moral lessons but about systemic cultural change. By embedding ethical values into the curriculum, equipping teachers, incentivizing civic engagement, monitoring outcomes, and collaborating across sectors, policymakers can cultivate a generation that not only rejects corruption but actively promotes integrity as a societal norm.

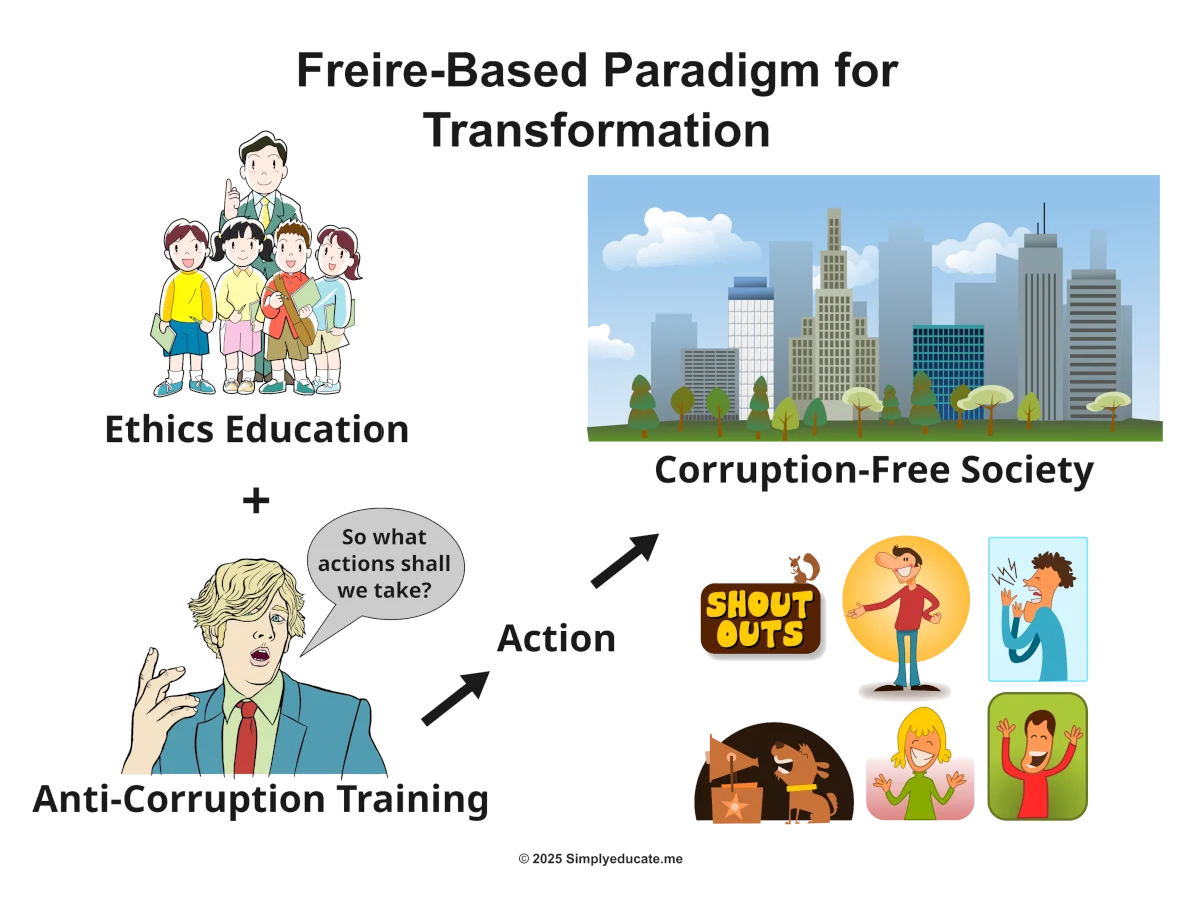

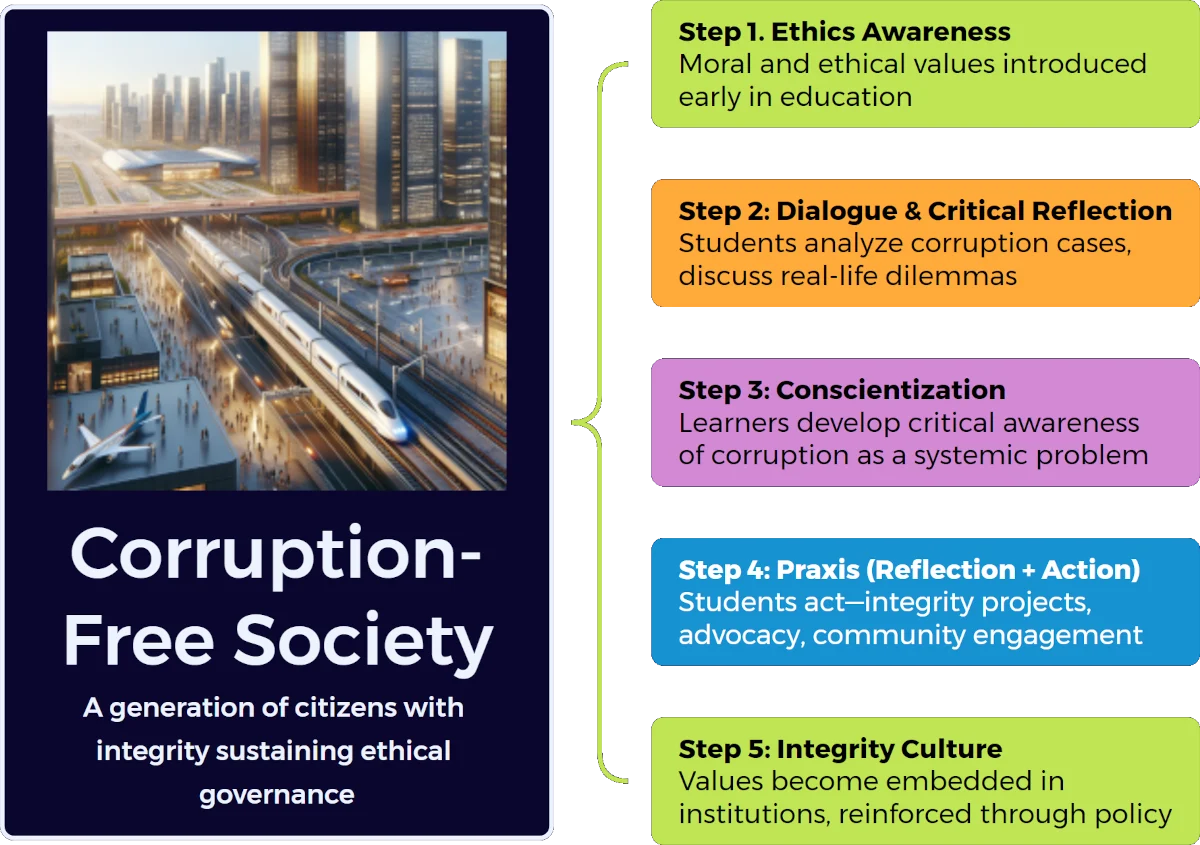

Diagram: Transformative Path to a Corruption-Free Society (Freirean Model)

Here is a simple step-by-step diagram representation to a corruption-free society using the Freirean Model to guide the implementation of a curriculum integrating ethics education as part of a national-level initiative:

Using Paulo Freire’s model, the path to a corruption-free society begins with ethics awareness in early education, where learners are introduced to moral values and honesty. This foundation is strengthened through dialogue and critical reflection, as students analyze corruption cases and debate real-life dilemmas. From this process emerges conscientization, or the development of critical awareness that corruption is not just individual misconduct but a systemic issue. Learners then move to praxis, where reflection is paired with concrete action through integrity projects, advocacy, and community engagement.

Over time, these practices foster an integrity culture, with values embedded in institutions and reinforced through policy, ultimately leading to a generation of citizens committed to sustaining ethical governance and a corruption-free society.

Conclusion

Ethics education and anti-corruption training are not supplementary subjects but transformative tools that can re-shape society. By adopting a Freirean approach—grounded in dialogue, critical consciousness, and action—the education system can nurture a young generation capable of resisting corruption and promoting integrity.

For graduate students of public administration, this framework offers both a theoretical grounding and a practical roadmap. For policymakers, it provides a long-term strategy that goes beyond enforcement to address corruption at its roots: the moral fabric of society.

You may download a sample policy brief based on the discussion in this article below:

Policy Brief: Embedding Ethics Education to Curb Corruption in the Philippines

Reference

Suwastika, I. W. K., Srinadi, N. L. P., & Hermawan, D. (2025). Ethics and Anti-Corruption Education A Systematic Review of The Role of Education in Shaping the Integrity of the Young Generation. Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Holistik, 4(2), 101-118.